Read the first chapter of The Paying Guests

The Barbers had said they would arrive by three. It was like waiting to begin a journey, Frances thought. She and her mother had spent the morning watching the clock, unable to relax. At half-past two she had gone wistfully over the rooms for what she’d supposed was the final time; after that there had been a nerving-up, giving way to a steady deflation, and now, at almost five, here she was again, listening to the echo of her own footsteps, feeling no sort of fondness for the sparsely furnished spaces, impatient simply for the couple to arrive, move in, get it over with.

She stood at a window in the largest of the rooms—the room which, until recently, had been her mother’s bedroom, but was now to be the Barbers’ sitting-room—and stared out at the street. The afternoon was bright but powdery. Flurries of wind sent up puffs of dust from the pavement and the road. The grand houses opposite had a Sunday blankness to them—but then, they had that every day of the week. Around the corner there was a large hotel, and motor-cars and taxi-cabs occasionally came this way to and from it; sometimes people strolled up here as if to take the air. But Champion Hill, on the whole, kept itself to itself. The gardens were large, the trees leafy. You would never know, she thought, that grubby Camberwell was just down there. You’d never guess that a mile or two further north lay London, life, glamour, all that.

How young they looked! The men seemed no more than boys

The sound of a vehicle made her turn her head. A tradesman’s van was approaching the house. This couldn’t be them, could it? She’d expected a carrier’s cart, or even for the couple to arrive on foot—but, yes, the van was pulling up at the kerb, with a terrific creak of its brake, and now she could see the faces in its cabin, dipped and gazing up at hers: the driver’s and Mr Barber’s, with Mrs Barber’s in between. Feeling trapped and on display in the frame of the window, she lifted her hand, and smiled.

This is it, then, she said to herself, with the smile still in place.

It wasn’t like beginning a journey, after all; it was like ending one and not wanting to get out of the train. She pushed away from the window and went downstairs, calling as brightly as she could from the hall into the drawing-room, ‘They’ve arrived, Mother!’

By the time she had opened the front door and stepped into the porch the Barbers had left the van and were already at the back of it, already unloading their things. The driver was helping them, a young man dressed almost identically to Mr Barber in a blazer and a striped neck-tie, and with a similarly narrow face and ungreased, week-endy hair, so that for a moment Frances was uncertain which of the two was Mr Barber. She had met the couple only once, nearly a fortnight ago. It had been a wet April evening and the husband had come straight from his office, in a mackintosh and bowler hat.

But now she recalled his gingery moustache, the reddish gold of his hair. The other man was fairer. The wife, whose outfit before had been sober and rather anonymous, was wearing a skirt with a fringe to it and a crimson jersey. The skirt ended a good six inches above her ankles. The jersey was long and not at all clinging, yet somehow revealed the curves of her figure. Like the men, she was hatless. Her dark hair was short, curling forward over her cheeks but shingled at the nape of her neck, like a clever black cap.

How young they looked! The men seemed no more than boys, though Frances had guessed, on his other visit, that Mr Barber must be twenty-six or -seven, about the same age as herself. Mrs Barber she’d put at twenty-three. Now she wasn’t so sure. Crossing the flagged front garden she heard their excited, unguarded voices. They had drawn a trunk from the van and set it unsteadily down; Mr Barber had apparently caught his fingers underneath it. ‘Don’t laugh!’ she heard him cry to his wife, in mock-complaint. She remembered, then, their ‘refined’ elocution-class accents.

Mrs Barber was reaching for his hand. ‘Let me see. Oh, there’s nothing.’

He snatched the hand back. ‘There’s nothing now. You just wait a bit. Christ, that hurts!’

The other man rubbed his nose. ‘Look out.’ He had seen Frances at the garden gate. The Barbers turned, and greeted her through the tail of their laughter—so that the laughter, not very comfortably, somehow attached itself to her.

‘Here you are, then,’ she said, joining the three of them on the pavement.

Mr Barber, still almost laughing, said, ‘Yes, here we are! Bringing down the character of the street already, you see.’

‘Oh, my mother and I do that.’

Mrs Barber spoke more sincerely. ‘We’re sorry we’re late, Miss Wray. The time just flew! You haven’t been waiting? You’d think we’d come from John o’ Groats or somewhere, wouldn’t you?’

Perhaps her tone was rather a cool one. The three young people looked faintly chastened, and with a glance at his injured knuckles Mr Barber returned to the back of the van.

They had come from Peckham Rye, about two miles away. Frances said, ‘Sometimes the shortest journeys take longest, don’t they?’

‘They do,’ said Mr Barber, ‘if Lilian’s involved in them. Mr Wismuth and I were ready at one.—This is my friend Charles Wismuth, who’s kindly lent us the use of his father’s van for the day.’

‘You weren’t ready at all!’ cried Mrs Barber, as a grinning Mr Wismuth moved forward to shake Frances’s hand. ‘Miss Wray, they weren’t, honestly!’

‘We were ready and waiting, while you were still sorting through your hats!’

‘At any rate,’ said Frances, ‘you are here now.’

Perhaps her tone was rather a cool one. The three young people looked faintly chastened, and with a glance at his injured knuckles Mr Barber returned to the back of the van. Over his shoulder Frances caught a glimpse of what was inside it: a mess of bursting suitcases, a tangle of chair and table legs, bundle after bundle of bedding and rugs, a portable gramophone, a wicker birdcage, a bronze-effect ashtray on a marbled stand . . . The thought that all these items were about to be brought into her home—and that this couple, who were not quite the couple she remembered, who were younger, and brasher, were going to bring them, and set them out, and make their own home, brashly, among them—the thought brought on a flutter of panic. What on earth had she done? She felt as though she was opening up the house to thieves and invaders.

But there was nothing else for it, if the house were to be kept going at all. With a determined smile she went closer to the van, wanting to help.

The men wouldn’t let her. ‘You mustn’t think of it, Miss Wray.’

‘No, honestly, you mustn’t,’ said Mrs Barber. ‘Len and Charlie will do it. There’s hardly anything, really.’ And she gazed down at the objects that were accumulating around her, tapping at her mouth with her fingers.

Frances remembered that mouth now: it was a mouth, as she’d put it to herself, that seemed to have more on the outside than on the in. It was touched with colour today, as it hadn’t been last time, and Mrs Barber’s eyebrows, she noticed, were thinned and shaped. The stylish details made her uneasy along with everything else, made her feel old-maidish, with her pinned-up hair and her angles, and her blouse tucked into her high-waisted skirt, after the fashion of the War, which was already four years over. Seeing Mrs Barber, a tray of houseplants in her arms, awkwardly hooking her wrist through the handle of a raffia hold-all, she said, ‘Let me take that bag for you, at least.’

‘Oh, I can do it!’

‘Well, I really must take something.’

Finally, noticing Mr Wismuth just handing it out of the van, she took the hideous stand-ashtray, and went across the front garden with it to hold open the door of the house. Mrs Barber came after her, stepping carefully up into the porch.

At the threshold itself, however, she hesitated, leaning over the ferns in her arms to look into the hall, and to smile.

‘It’s just as nice as I remembered.’

Frances turned. ‘It is?’ She could see only the dishonesty of it all: the scuffs and tears she had patched and disguised; the gap where the long-case clock had stood, which had had to be sold six months before; the dinner-gong, bright with polish, that hadn’t been rung in years and years. Turning back to Mrs Barber, she found her still waiting at the step. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘you’d better come in. It’s your house too, now.’

Mrs Barber’s shoulders rose; she bit her lip and raised her eyebrows in a pantomime of excitement. She stepped cautiously into the hall, where the heel of one of her shoes at once found an unsteady tile on the black-and-white floor and set it rocking. She tittered in embarrassment: ‘Oh, dear!’

Frances’s mother appeared at the drawing-room door. Perhaps she had been standing just inside it, getting up the enthusiasm to come out.

‘Welcome, Mrs Barber.’ Smiling, she came forward. ‘What pretty plants. Rabbit’s foot, aren’t they?’

Mrs Barber manoeuvred her tray and her hold-all so as to be able to offer her hand. ‘I’m afraid I don’t know.’

‘I believe they are. Rabbit’s foot—so pretty. You found your way to us all right?’

‘Yes, but I’m sorry we’re so late!’

‘Well, it doesn’t matter to us. The rooms weren’t going to run away. We must give you some tea.’

‘Oh, you mustn’t trouble.’

‘But you must have tea. One always wants tea when one moves house; and one can never find the teapot. I’ll see to it, while my daughter takes you upstairs.’ She gazed dubiously at the ashtray. ‘You’re helping too, are you, Frances?’

‘It seemed only fair to, with Mrs Barber so laden.’

‘Oh, no, you mustn’t help at all,’ said Mrs Barber—adding, with another titter, ‘We don’t expect that!’

Frances, going ahead of her up the staircase, thought: How she laughs!

Up on the wide landing they had to pause again. The door on their left was closed—that was the door to Frances’s bedroom, the only room up here which was to stay in her and her mother’s possession—but the other doors all stood open, and the late-afternoon sunlight, richly yellow now as the yolk of an egg, was streaming in through the two front rooms as far almost as the staircase. It showed up the tears in the rugs, but also the polish on the Regency floorboards, which Frances had spent several back-breaking mornings that week bringing to the shine of dark toffee; and Mrs Barber didn’t like to cross the polish in her heels. ‘It doesn’t matter,’ Frances told her. ‘The surface will dull soon enough, I’m afraid.’ But she answered firmly, ‘No, I don’t want to spoil it’—putting down her bag and her tray of plants and slipping off her shoes.

She left small damp prints on the wax. Her stockings were black ones, blackest at the toe and at the heel, where the reinforcing of the silk had been done in fancy stepped panels. While Frances hung back and watched she went into the largest of the rooms, looking around it in the same noticing, appreciative manner in which she had looked around the hall; smiling at every antique detail.

‘What a lovely room this is. It feels even bigger than it did last time. Len and I will be lost in it. We’ve only had our bedroom really, you see, at his parents’. And their house is—well, not like this one.’ She crossed to the left-hand window—the window at which Frances had been standing a few minutes before—and put up a hand to shade her eyes. ‘And look at the sun! It was cloudy when we came before.’

But then she moved back, and drew in her gaze; and her voice changed, became indulgent. ‘Oh, look at Len. Look at him complaining. Isn’t he puny!’

Frances joined her at last. ‘Yes, you get the best of the sun in this room. I’m afraid there isn’t much in the way of a view, even though we’re so high.’

‘Oh, but you can see a little, between the houses.’

‘Between the houses, yes. And if you peer south—that way’— she pointed—‘you can make out the towers of the Crystal Palace. You have to go nearer to the glass . . . You see them?’

They stood close together for a moment, Mrs Barber with her face an inch from the window, her breath misting the glass. Her dark-lashed eyes searched, then fixed. ‘Oh, yes!’ She sounded delighted.

But then she moved back, and drew in her gaze; and her voice changed, became indulgent. ‘Oh, look at Len. Look at him complaining. Isn’t he puny!’ She tapped at the window, and called and gestured. ‘Let Charlie take that! Come and see the sun! The sun. Can you see? The sun!’ She dropped her hand. ‘He can’t understand me. Never mind. How funny it is, seeing our things set out like that. How poor it all looks! Like a penny bazaar. What must your neighbours be thinking, Miss Wray?’

What indeed? Already Frances could see sharp-eyed Mrs Dawson over the way, pretending to be fiddling with the bolt of her drawing-room window. And now here was Mr Lamb from High Croft further down the hill, pausing as he passed to blink at the stuffed suitcases, the blistered tin trunks, the bags, the baskets and the rugs that Mr Barber and Mr Wismuth, for convenience, were piling on the low brick garden wall.

She saw the two men give him a nod, and heard their voices: ‘How do you do?’ He hesitated, unable to place them—perhaps thrown by the stripes on their ‘club’ ties.

‘We ought to go and help,’ she said.

Mrs Barber answered, ‘Oh, I will.’

But when she left the room it was to wander into the bedroom beside it. And she went from there to the last of the rooms, the small back room facing Frances’s bedroom across the return of the landing and the stairs—the room which Frances and her mother still called Nelly and Mabel’s room, even though they hadn’t had Nelly, Mabel, or any other live-in servant since the munitions factories had finally lured them away in 1916. This was done up now as a kitchen, with a dresser and a sink, with gaslight and a gas stove and a shilling-in-the-slot meter. Frances herself had varnished the wallpaper; she had stained the floor here, rather than waxing it. The cupboard and the aluminium-topped table she had hauled up from the scullery, one day when her mother wasn’t at home to have to watch her do it.

She had done her best to get it all right. But seeing Mrs Barber going about, taking possession, determining which of her things would go here, which there, she felt oddly redundant—as if she had become her own ghost. She said awkwardly, ‘Well, if you’ve everything you need, I’ll see how your tea’s coming along. I shall be just downstairs if there’s any sort of problem. Best to come to me rather than to my mother, and—Oh.’ She stopped, and reached into her pocket. ‘I’d better give you these, hadn’t I, before I forget.’

She drew out keys to the house: two sets, on separate ribbons. It took an effort to hand them over, actually to put them into the palm of this woman, this girl—this more or less perfect stranger, who had been summoned into life by the placing of an advertisement in the South London Press. But Mrs Barber received the keys with a gesture, a dip of her head, to show that she appreciated the significance of the moment. And with unexpected delicacy she said, ‘Thank you, Miss Wray. Thank you for making everything so nice. I’m sure Leonard and I will be happy here. Yes, I’m certain we will. I have something for you too, of course,’ she added, as she took the keys to her hold-all to stow them away. She brought back a creased brown envelope.

It was two weeks’ rent. Fifty-eight shillings: Frances could already hear the rustle of the pound notes and the slide and chink of the coins. She tried to arrange her features into a businesslike expression as she took the envelope from Mrs Barber’s hand, and she tucked it in her pocket in a negligent sort of way—as if anyone, she thought, could possibly be deceived into thinking that the money was a mere formality, and not the essence, the shabby heart and kernel, of the whole affair.

Downstairs, while the men went puffing past with a treadle sewing-machine, she slipped into the drawing-room, just to give herself a quick peek at the cash. She parted the gum of the envelope and—oh, there it all was, so real, so present, so hers, she felt she could dip her mouth to it and kiss it. She folded it back into her pocket, then almost skipped across the hall and along the passage to the kitchen.

Her mother was at the stove, lifting the kettle from the hot-plate with the faintly harried air she always had when left alone in the kitchen; she might have been a passenger on a stricken liner who’d just been bundled into the engine room and told to man the gauges. She gave the kettle up to Frances’s steadier hand, and went about gathering the tea-things, the milk-jug, the bowl of sugar. She put three cups and saucers on a tray for the Barbers and Mr Wismuth; and then she hesitated with two more saucers raised. She spoke to Frances in a whisper. ‘Ought we to drink with them, do you think?’

Frances hesitated too. What were the rules?

Oh, who cared! They had got the money now. She plucked the saucers from her mother’s fingers. ‘No, let’s not start that sort of thing off. There’ll be no end to it if we do. We can keep to the drawing-room; they can have their tea up there. I’ll give them a plate of biscuits to go with it.’ She drew the lid from the tin and dipped in her hand.

Once again, however, she dithered. Were biscuits absolutely necessary? She put three on a plate, set the plate beside the tea-pot—then changed her mind and took it off again.

But then she thought of nice Mrs Barber, going carefully over the polish; she thought of the fancy heels on her stockings; and returned the plate to the tray.

The men went up and down the stairs for another thirty minutes, and for some time after that boxes and cases could be heard being shifted about, furniture was dragged and wheeled, the Barbers called from room to room; once there came a blast of music from their portable gramophone, that made Frances and her mother look at one another, aghast. But Mr Wismuth left at six, tapping at the drawing-room door as he went, wanting to say a polite goodbye; and with his departure the house grew calmer.

Even the fifty-eight shillings in her pocket began to lose their magic power; it was dawning on her just how thoroughly she would have to earn them.

It was inescapably not, however, the house that it had been two hours before. Frances and her mother sat with books at the French windows, ready to eke out the last of the daylight—having got used, in the past few years, to making little economies like that. But the room—a long, handsome room, running the depth of the house, divided by double doors which, in spring and summer, they left open—had two of the Barbers’ rooms above it, their bedroom and their kitchen, and Frances, turning pages, found herself aware of the couple overhead, as conscious of their foreign presence as she might have been of a speck in the corner of her eye. For a while they moved about in the bedroom; she could hear drawers being opened and closed. But then one of them entered their kitchen and, after a purposeful pause, there came a curious harsh dropping sound, like the clockwork gulp of a metal monster. One gulp, two gulps, three gulps, four: she stared at the ceiling, baffled, until she realised that they were simply putting shillings in the meter. Water was run after that, and then another odd noise started, a sort of pulse or quick pant—the meter again, presumably, as the gas ran through it. Mrs Barber must be boiling a kettle. Now her husband had joined her. There was conversation, laughter … Frances caught herself thinking, as she might have done of guests, Well, they’re certainly making themselves at home.

Then she took in the implication of the words, and her heart, very slightly, sank.

While she was out in the kitchen assembling a cold Sunday supper, the couple came down, and tapped at the door, first the wife and then the husband: the WC was an outside one, across the yard from the back door, and they had to pass through the kitchen to get to it. They came grimacing with apology; Frances apologised, too. She supposed that the arrangement was as inconvenient to them as it was to her. But with each encounter, her confidence wobbled a little more. Even the fifty-eight shillings in her pocket began to lose their magic power; it was dawning on her just how thoroughly she would have to earn them. She simply hadn’t prepared herself for the oddness of the sound and the sight of the couple going about from room to room as if the rooms belonged to them. When Mr Barber, for example, headed back upstairs after his visit to the yard, she heard him pause in the hall. Wondering what could be delaying him, she ventured a look along the passage, and saw him gazing at the pictures on the walls like a man in a gallery. Leaning in for a better look at a steel engraving of Ripon Cathedral he put his fingers to his pocket and brought out a matchstick, with which he began idly picking his teeth.

She didn’t mention any of this to her mother. The two of them kept brightly to their evening routine, playing a couple of games of backgammon once supper had been eaten, taking a cup of watery cocoa at a quarter to ten, then starting on the round of chores—the gatherings, the turnings-down, the cushion-plumpings and the lockings-up—with which they eased their way to bed.

Frances’s mother said good night first. Frances herself spent some time in the kitchen, tidying, seeing to the stove. She visited the WC, she laid the table for breakfast; she took the milk-can out to the front garden, put it to hang beside the gate. But when she had returned to the house and was lowering the gas in the hall she noticed a light still shining under her mother’s door. And though she wasn’t in the habit of calling in on her mother after she had gone to bed, somehow, tonight, that bar of light beckoned. She went across to it, and tapped.

‘May I come in?’

Her mother was sitting up in bed, her hair unpinned and put into plaits. The plaits hung down like fraying ropes: until the War her hair had been brown, as pure a brown as Frances’s, but it had faded in the past few years, growing coarser in the process, and now, at fifty-five, she had the white head of an old lady; only her brows remained dark and decided above her handsome hazel eyes. She had a book in her lap, a little railway thing called Puzzles and Conundrums: she had been trying out answers to an acrostic.

She let the book sink when Frances appeared, and gazed at her over the lenses of her reading-glasses.

‘Everything all right, Frances?’

‘Yes. Just thought I’d look in. Go on with your puzzle, though.’ ‘Oh, it’s only a nonsense to help me off to sleep.’

But she peered at the page again, and an answer must have come to her: she tried out the word, her lips moving along with her pencil. The unoccupied half of bed beside her was flat as an ironing-board. Frances kicked off her slippers, climbed on to it, and lay back with her hands behind her head.

This room had still been the dining-room, a month before. Frances had painted over the old red paper and rearranged the pictures, but, as with the new kitchen upstairs, the result was not quite convincing. Her mother’s bits of bedroom furniture seemed to her to be sitting as tensely as unhappy visitors: she could feel them pining for their grooves and smooches in the floor of the room above. Some of the old dining-room furniture had had to stay in here too, for want of anywhere else to put it, and the effect was an overcrowded one, with a suggestion of elderliness and a touch—just a touch—of the sick chamber. It was the sort of room she could remember from childhood visits to ailing great-aunts. All it really lacked, she thought, was the whiff of a commode, and the little bell for summoning the whiskery spinster daughter.

She quickly turned her back on that image. Upstairs, one of the Barbers could be heard crossing their sitting-room floor—Mr Barber, she guessed it was, from the bounce and briskness of the tread; Mrs Barber’s was more sedate. Looking up at the ceiling, she followed the steps with her eyes.

Beside her, her mother also gazed upward. ‘A day of great changes,’ she said with a sigh. ‘Are they still unpacking their things? They’re excited, I suppose. I remember when your father and I first came here, we were just the same. They seem pleased with the house, don’t you think?’ She had lowered her voice. ‘That’s something, isn’t it?’

Frances answered in the same almost furtive tone. ‘She does, at any rate. She looks like she can’t believe her luck. I’m not so sure about him.’

‘Well, it’s a fine old house. And a home of their own: that means a great deal when one is first married.’

‘Oh, but they’re hardly newly-weds, are they? Didn’t they tell us that they’d been married for three years? Straight out of the War, I suppose. No children, though.’

Her mother’s tone changed slightly. ‘No.’ And after a second, the one thought plainly having led to the next, she added, ‘Such a pity that the young women today all feel they must make up.’

Frances reached for the book and studied the acrostic. ‘Isn’t it? And on a Sunday, too.’

She felt her mother’s level gaze. ‘Don’t imagine that I can’t tell when you are making fun of me, Frances.’

Upstairs, Mrs Barber laughed. Something light was dropped or thrown and went skittering across the boards. Frances gave up on the puzzle. ‘What do you think her background can be?’

Her mother had closed the book and was putting it aside. ‘Whose?’

She gave a jerk of her chin. ‘Mrs B’s. I should say her father’s some sort of branch manager, shouldn’t you? A mother who’s rather “nice”. “Indian Love Lyrics” on the gramophone, perhaps a brother doing well for himself in the Merchant Navy. Piano lessons for the girls. An outing to the Royal Academy once a year . . . ’ She began to yawn. Covering her mouth with the back of her wrist, she went on, through the yawn, ‘One good thing, I suppose, about their being so young: they’ve only his parents to compare us with. They won’t know that we really haven’t a clue what we’re doing. So long as we act the part of landladies with enough gusto, then landladies is what we will be.’

Her mother looked pained. ‘How baldly you put it! You might be Mrs Seaview, of Worthing.’

‘Well, there’s no shame in being a landlady; not these days. I for one aim to enjoy landladying.’

‘If you would only stop saying the word!’

Frances smiled. But her mother was plucking at the silk binding of a blanket, a look of real distress beginning to creep into her expression; she was an inch, Frances knew, from saying, ‘Oh, it would break your dear father’s heart!’ And since even now, nearly four years after his death, Frances couldn’t think of her father without wanting to grind her teeth, or swear, or leap up and smash something, she hastily turned the conversation. Her mother was involved in the running of two or three local charities: she asked after those. They spoke for a time about a forthcoming bazaar.

Once she saw her mother’s face clear, become simply tired and elderly, she got to her feet.

‘Now, have you everything you need? You don’t want a biscuit, in case you wake?’

And just like that, like a knee or an elbow receiving a blow on the wrong spot, her heart was jangling.

Her mother began to arrange herself for sleep. ‘No, I don’t want a biscuit. But you may put out the light for me, Frances.’

She lifted the plaits away from her shoulders and settled her head on her pillow. Her glasses had left little bruise-like dints on the bridge of her nose. As Frances reached to the lamp there were more footsteps in the room above; and then her hazel eyes returned to the ceiling.

‘It might be Noel or John Arthur up there,’ she murmured, as the light went down.

And, yes, thought Frances a moment later, lingering in the shadowy hall, it might be; for she could smell tobacco smoke now, and hear some sort of masculine muttering up on the landing, along with the tap of a slippered male foot . . . And just like that, like a knee or an elbow receiving a blow on the wrong spot, her heart was jangling. How grief could catch one out, still! She had to stand at the foot of the stairs while the fit of sorrow ran through her. But if only, she thought, as she began to climb—she hadn’t thought it in ages—if only, if only she might turn the stair and find one of her brothers at the top—John Arthur, say, looking lean, looking bookish, looking like a whimsical monk in his brown Jaeger dressing-gown and Garden City sandals.

There was no one save Mr Barber, a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, his jacket off, his cuffs rolled back; he was fiddling with a nasty thing he had evidently just hung on the landing wall, a combination barometer-and-clothes-brush set with a lurid orangey varnish. But lurid touches were everywhere, she saw with dismay. It was as if a giant mouth had sucked a bag of boiled sweets and then given the house a lick. The faded carpet in her mother’s old bedroom was lost beneath pseudo-Persian rugs. The lovely pier-glass had been draped slant-wise with a fringed Indian shawl. A print on one of the walls appeared to be a Classical nude in the Lord Leighton manner. The wicker birdcage twirled slowly on a ribbon from a hook that had been screwed into the ceiling; inside it was a silk-and-feather parrot on a papier-mâché perch.

The landing light was turned up high, hissing away as if furious. Frances wondered if the couple had remembered that she and her mother were paying for that. Catching Mr Barber’s eye, she said, in a voice to match the dreadful brightness all around them, ‘Got everything straight, have you?’

He took the cigarette out of his mouth, stifling a yawn. ‘Oh, I’ve had enough of it for one day, Miss Wray. I did my bit, bringing up those blessed boxes. I leave the titivating to Lilian. She loves all that sort of thing. She can titivate for England, she can.’

Frances hadn’t really looked at him properly before. She’d absorbed his manner, his ‘theme’—that facetious grumbling— rather than anything more tangible, more physical. Now, in the flat landing light, she took in the clerkly neatness of him. Without his shoes he was only an inch or two taller than she. ‘Puny,’ his wife had called him; but there was too much life in him for that. His face was textured with gingery stubble and with little pimple scars, his jaw was narrow, his teeth slightly crowded, his eyes had sandy, near-invisible lashes. But the eyes themselves were very blue, and they somehow made him handsome, or almost-handsome—more handsome, anyhow, than she had realised so far.

She looked away from him. ‘Well, I’m off to bed.’

He fought down another yawn. ‘Lucky you! I think Lily’s still decorating ours.’

‘I’ve put out the lights downstairs. The mantle in the hall has a bit of a trick to it, so I thought I’d better do it. I ought to have shown you, I suppose.’

He said helpfully, ‘Show me now, if you like.’

‘Well, my mother’s trying to sleep. Her room, you know, is just at the bottom of the stairs—’

‘Ah. Show me tomorrow, then.’

‘I will. I’m afraid it’ll be dark, though, if you or Mrs Barber need to go down again tonight.’

‘Oh, we’ll find our way.’

‘Take a lamp, perhaps.’

‘That’s an idea, isn’t it? Or, I tell you what.’ He smiled. ‘I’ll send Lil down first, on a rope. Any trouble and she can . . . give me a tug.’ He kept his gaze on hers as he spoke, in a playful sort of way. But there was something to his manner, something vaguely unsettling. She hesitated about replying and he raised his cigarette, turning his head to take a puff of it, twisting his mouth out of its smile to direct away the smoke; but still holding her gaze with those lively blue eyes of his.

Then, with a blink, his manner changed. The door to his bedroom was drawn open and his wife appeared. She had a picture in her hands—another Lord Leighton nude, Frances feared it was— and the sight of it brought on one of his mock-complaints.

‘Are you still at it, woman? Blimey O’Reilly!’

She gave Frances a smile. ‘I’m only making things look nice.’ ‘Well, poor Miss Wray wants to go to bed. She’s come to complain about the noise.’

Her face fell. ‘Oh, Miss Wray, I’m so sorry!’

Frances said quickly, ‘You haven’t been noisy at all. Mr Barber is teasing.’

‘I meant to save it all for tomorrow. But now I’ve started, I can’t stop.’

The landing felt impossibly crowded to Frances with them all standing there like that. Would the three of them have to meet, exchange pleasantries, every night? ‘You must take as long as you need,’ she said in her false, bright way. ‘At least—’ She’d begun to move towards her door, but paused. ‘You will remember, won’t you, about my mother, in the room downstairs?’

‘Oh, yes, of course,’ said Mrs Barber. And, ‘Of course we will,’ echoed her husband, in apparent earnestness.

Frances wished she’d said nothing. With an awkward ‘Well, good night,’ she let herself into her room. She left the door ajar for a moment while she lit her bedroom candle, and as she closed it she saw Mr Barber, puffing on his cigarette, looking across the landing at her; he smiled and moved away.

Once the door was shut and the key turned softly in the lock, she began to feel better. She kicked off her slippers, took off her blouse, her skirt, her underthings and stockings . . . and at last, like a portly matron letting out the laces of her stays, she was herself again. Raising her arms in a stretch, she looked around the shadowy room. How beautifully calm and uncluttered it was! The mantelpiece had two silver candlesticks on it and nothing else. The bookcase was packed but tidy, the floor dark with a single rug; the walls were pale—she’d removed the paper and used a white distemper instead. Even the framed prints were unbusy: a Japanese interior, a Friedrich landscape, the latter just visible in the candlelight, a series of snowy peaks dissolving into a violet horizon.

With a yawn, she felt for the pins in her hair and pulled them free. She filled her bowl with water, ran a flannel over her face, around her neck and under her arms; she cleaned her teeth, rubbed Vaseline into her cheeks and ruined hands. And then, because all this time she’d been able to smell Mr Barber’s cigarette and the scent was making her restless, she opened the drawer of her nightstand and brought out a packet of papers and a tin of tobacco. She rolled a neat little fag, lit it by the flame of her candle, climbed into bed with it, then blew the candle out. She liked to smoke like this, naked in the cool sheets, with only the hot red tip of a cigarette to light her fingers in the dark.

Tonight, of course, the room was not quite dark: light was leaking in from the landing, a thin bright pool of it beneath her door. What were they doing out there now? She could hear the murmur of their voices. They were debating where to hang the wretched picture—were they? If they started banging in a nail she would have to go and say something. If they left the landing light burning so furiously she’d have to say something, too. She began trying out phrases in her head.

I’m sorry to have to raise this matter—

Do you remember we discussed—?

Perhaps we might—

It might be best if—

I’m afraid I made a mistake.

No, she wouldn’t think that! It was too late for that. It was—oh, years and years too late for that.

She slept well, in the end. She awoke at six the next morning, when the first distant factory whistle went off. She dozed for an hour, and was finally jolted out of a complicated dream by a hectic drill-like noise she couldn’t at first identify; it was the ring, she realised blearily, of the Barbers’ alarm clock. It seemed no time at all since she had lain there listening to the couple make their murmuring way to bed. Now she got the reverse of it, as they emerged to mutter and yawn, to creep downstairs and out to the yard, to clatter about in their kitchen, brewing tea, frying a breakfast. She made herself pay attention to it all, every hiss and splutter of the bacon, every tap of the razor against the sink. She had to accommodate it, fit herself around it: the new start to her day.

She’d remembered the fifty-eight shillings. While Mr Barber was gathering his outdoor things she rose and quietly dressed. He left the house at just before eight, by which time his wife had returned to their bedroom; Frances gave it a couple of minutes, so as not to be too obvious about it, then unlocked her door and went downstairs. She raked out the ashes of the stove and got a new fire going. She crossed the yard, returned to the house to greet her mother, make tea, boil eggs. But all the time she worked, her mind was busy with calculations. Once she and her mother had had their breakfast and the dining-table had been cleared she settled herself down with her book of accounts and ran through the bundle of bills that, over the last half-year, had been steadily accumulating at the back of it.

The butcher and the fishmonger, she thought, ought to be given large sums at once. The laundryman, the baker and the coal-merchants could be kept at bay with smaller amounts. The house-rates would be due in a few weeks’ time, along with the quarterly gas bill; the bill would be higher than usual, because it would contain the charge for the cooker and the meter and the pipes and connections that had been installed upstairs. There was still money to be paid, too, for some of the other preparations that had had to be made for the Barbers—for things like varnish and distemper. It would be three or four months—August or September at the earliest, she reckoned—before their rent would show itself in the family bank account as clear profit.

Still, August or September was a great deal better than never, and she put her account book away with her spirits lifting. The baker’s man came, shortly followed by the butcher’s boy: for once she was able to take the bread and the meat as if really entitled to them and not somehow involved in the shady reception of stolen goods. The meat was neck of lamb; that could go into a hot-pot later. She had no real interest in food, neither in preparing nor in eating it, but she had developed a grudging aptitude for cookery during the War; she enjoyed, anyhow, the practical challenge of making one cheap cut of meat do for several different dishes. She felt similarly about housework, liking best those rather out-of-the-way tasks—stripping the stove, cleaning stair-rods—that needed planning, strategy, chemicals, special tools.

Most of her chores, inevitably, were more mundane. The house was full of inconveniences, bristling with picture rails and plasterwork and elaborate skirting-boards that had to be dusted more or less daily. The furniture was all of dark woods that had to be dusted regularly, too. Her father had had a passion for ‘Olde England’, not at all in keeping with the Regency whimsies of the villa itself, and there was a Jacobean chair or chest in every odd corner. ‘Father’s collection’, the pieces had been known as, while her father was alive; a year after his death Frances had had them valued and had discovered them all to be Victorian fakes. The dealer who’d bought the long-case clock had offered her three pounds for the lot. She would have been glad to pocket the money and have the damn things carted away, but her mother had grown upset at the prospect. ‘Whether they’re genuine or not,’ she’d said, ‘they have your father’s heart in them.’ ‘They have his stupidity, more like,’ Frances had answered, though not aloud. So the furniture remained, which meant that several times a week she had to go scuttling around like a crab, rubbing her duster over the barley-twist curves of wonky table legs and the scrolls and lozenges of rough-hewn chairs.

Where on earth did the dust come from? It seemed to her that the house must produce it, as flesh oozes sweat.

The very heaviest of the housework she saved for those mornings and afternoons when she could rely on her mother being safely out of the way. Since today was a Monday, she had ambitious plans. Her mother spent Monday mornings seeing to bits of parish business with the local vicar, and Frances could ‘do’ the entire ground floor in her absence.

She began the moment the front door closed, rolling up her sleeves, tying on an apron, covering her hair. She saw to her mother’s bedroom first, then moved to the drawing-room for sweeping, dusting—endless dusting, it felt like. Where on earth did the dust come from? It seemed to her that the house must produce it, as flesh oozes sweat. She could beat and beat a rug or a cushion, and still it would come. The drawing-room had a china cabinet in it, with glass doors, tightly closed, but even the things inside grew dusty and had to be wiped. Just occasionally she longed to take each fiddly porcelain cup and saucer and break it in two. Once, in sheer frustration, she had snapped off the head of one of the apple-cheeked Staffordshire figures: it still sat a little crookedly, from where she had hurriedly glued it back on.

She didn’t feel like that today. She worked briskly and efficiently, taking her brush and pan from the drawing-room to the top of the stairs and making her way back down, a step at a time; after that she filled a bucket with water, fetched her kneeling-mat, and began to wash the hall floor. Vinegar was all she used. Soap left streaks on the black tiles. The first, wet rub was important for loosening the dirt, but it was the second bit that really counted, passing the wrung cloth over the floor in one supple, unbroken movement . . . There! How pleasing each glossy tile was. The gloss would fade in about five minutes as the surface dried; but everything faded. The vital thing was to make the most of the moments of brightness. There was no point dwelling on the scuffs. She was young, fit, healthy. She had—what did she have? Little pleasures like this. Little successes in the kitchen. The cigarette at the end of the day. Cinema with her mother on a Wednesday. Regular trips into Town. There were spells of restlessness now and again; but any life had those. There were longings, there were desires . . . But they were physical matters mostly, and she had no last-century inhibitions about dealing with that sort of thing. It was amazing, in fact, she reflected, as she repositioned her mat and bucket and started on a new stretch of tile, it was astonishing how satisfactorily the business could be taken care of, even in the middle of the day, even with her mother in the house, simply by slipping up to her bedroom for an odd few minutes, perhaps as a break between peeling parsnips or while waiting for dough to rise—

A movement at the turn of the staircase made her start. She had forgotten all about her lodgers. Now she looked up through the banisters to see Mrs Barber just coming uncertainly down.

She felt herself blush, as if caught out. But Mrs Barber was also blushing. Though it was well after ten, she was dressed in her nightgown still; she had some sort of satiny Japanese wrapper on top—a kimono, Frances supposed the thing was called—and her feet were bare inside Turkish slippers. She was carrying a towel and a sponge-bag. As she greeted Frances she tucked back a sleep-flattened curl of hair and said shyly, ‘I wondered if I might have a bath.’

‘Oh,’ said Frances. ‘Yes.’

‘But not if it’s a trouble. I fell back asleep after Len went to work, and—’

Frances began to get to her feet. ‘It’s no trouble. I shall have to light the geyser for you, that’s all. My mother and I don’t usually light it during the day. I should have said last night. Can you come across? You’ll have to hop.’ She moved her bucket. ‘Here’s a dry bit, look.’

Mrs Barber, however, had come further down the stairs, and her colour was deepening: she was gazing in a mortified way at the duster on Frances’s head, at her rolled-up sleeves and flaming hands, at the housemaid’s mat at her feet, still with the dents of her knees in it. Frances knew the look very well—she was bored to death with it, in fact—because she had seen it many times before: on the faces of neighbours, of tradesmen, and of her mother’s friends, all of whom had got themselves through the worst war in human history yet seemed unable for some reason to cope with the sight of a well-bred woman doing the work of a char. She said breezily, ‘You remember my saying about us not having help? I really meant it, you see. The only thing I draw the line at is laundry; most of that still gets sent out. But everything else, I take care of. The “brights”, the “roughs”—yes, I’ve all the lingo!’

Mrs Barber had begun to smile at last. But as she looked at the stretch of floor that was still to be washed, she grew embarrassed in a different sort of way.

‘I’m afraid Len and I must have made an awful mess yesterday. I wasn’t thinking.’

‘Oh,’ said Frances, ‘these tiles get dirty all by themselves. Everything in this house does.’

‘Once I’ve dressed, I’ll finish it for you.’

‘You’ll do nothing of the sort. You’ve your own rooms to care for. If you can manage without a maid, why shouldn’t I? Besides, you’d be amazed what a whiz I can be with a mop.—Here, let me help.’

Mrs Barber was on the bottom stair now and clearly doubtful about where to step to. After the slightest of hesitations, she took the hand that Frances offered, braced herself against her grip, then made the small spring forward to the unwashed side of the floor. Her kimono parted as she landed, exposing more of her nightdress, and giving an alarming suggestion of the rounded, mobile, unsupported flesh inside.

They went together through the kitchen and into the scullery. The bath was in there, beside the sink. It had a bleached wooden cover, used by Frances as a draining-board; with a practised movement she lifted this free and set it against the wall. The tub was an ancient one that had been several times re-enamelled, most recently by Frances herself, who was not quite sure of the result; the iron struck her, today especially, as having a faintly leprous appearance. The Vulcan geyser was also rather frightful, a greenish riveted cylinder on three bowed legs. It must have been the top of its manufacturer’s range in about 1870, but now looked like the sort of vessel in which someone in a Jules Verne novel might make a trip to the moon.

‘It has a bit of a temperament, I’m afraid,’ she told Mrs Barber as she explained the mechanism. ‘You have to turn this tap, but not this one; you might blow us sky-high if you do. The flame goes here.’ She struck a match. ‘Best to look the other way at this point. My father lost both his eyebrows doing this once.—There.’

The flame, with a whoosh, had found the gas. The cylinder began to tick and rattle. She frowned at it, her hands at her hips. ‘What a beast it is. I am sorry, Mrs Barber.’ She gazed right round the room, at the stone sink, the copper in the corner, the mortuary tiles on the wall. ‘I do wish this house was more up-to-date for you.’

But Mrs Barber shook her head. ‘Oh, please don’t wish that.’ She tucked back another curl of hair; Frances noticed the piercing for her earring, a little dimple in the lobe. ‘I like the house just as it is. It’s a house with a history, isn’t it? Things—well, they oughtn’t always to be modern. There’d be no character if they were.’

And there it was again, thought Frances: that niceness, that kindness, that touch of delicacy. She answered with a laugh. ‘Well, as far as character goes, I fear this house might be rather too much of a good thing. But—’ She spoke less flippantly. ‘I’m glad you like it. I’m very glad. I like it too, though I’m apt to forget that.—Now, we oughtn’t to let this geyser get hot without running some water, or there’ll be no house left to like, and no us to do the liking! Do you think you can manage? If the flame goes out—it sometimes does, I’m sorry to say—give me a call.’

Mrs Barber smiled, showing neat white teeth. ‘I will. Thank you, Miss Wray.’

Frances left her to it and returned to her wet floor. The scullery door was closed behind her, and quietly bolted.

But the door between the kitchen and the passage was propped open, and as Frances retrieved her cloth she could hear, very clearly, Mrs Barber’s preparations for her bath, the rattle of the chain against the tub, followed by the splutter and gush of the water. The gushing, it seemed to her, went on for a long time. She had told a fib about her and her mother’s use of the geyser: it was too expensive to light often; they drew their hot water from the boiler in the old-fashioned stove. They bathed, at most, once a week, frequently taking turns with the same bathwater. If Mrs Barber were to want baths like this on a daily basis, their gas bill might double.

But at last the flow was cut off. There came the splash of water and the rub of heels as Mrs Barber stepped into the tub, followed by a more substantial liquid thwack as she lowered herself down. After that there was a silence, broken only by the occasional echoey plink of drips from the tap.

Like the parted kimono, the sounds were unsettling; the silence was most unsettling of all. Sitting at her bureau a short time before, Frances had been picturing her lodgers in purely mercenary terms—as something like two great waddling shillings. But this, she thought, shuffling backward over the tiles, this was what it really meant to have lodgers: this odd, unintimate proximity, this rather peeled-back moment, where the only thing between herself and a naked Mrs Barber was a few feet of kitchen and a thin scullery door. An image sprang into her head: that round flesh, crimsoning in the heat.

She adjusted her pose on the mat, took hold of her cloth, and rubbed hard at the floor.

The steam was still beading the scullery walls when her mother returned at lunch-time. Frances told her about Mrs Barber’s bath, and she looked startled.

‘At ten o’clock? In her dressing-gown? You’re sure?’

‘Quite sure. A satin one, too. What a good job, wasn’t it, that you were visiting the vicar, and not the other way round?’

Her mother paled, but didn’t answer.

They ate their lunch—a cauliflower cheese—then settled down together in the drawing-room. Mrs Wray made notes for a parish newsletter. Frances worked her way through a basket of mending with The Times on the arm of her chair. What was the latest?

Awkwardly, she turned the inky pages. But it was the usual dismal stuff. Horatio Bottomley was off to the Old Bailey for swindling the public out of a quarter of a million. An MP was asking that cocaine traffickers be flogged. The French were shooting Syrians, the Chinese were shooting each other, a peace conference in Dublin had come to nothing, there’d been new murders in Belfast . . . But the Prince of Wales looked jolly on a fishing trip in Japan, and the Marchioness of Carisbrooke was about to host a ball ‘in aid of the Friends of the Poor’.—So that was all right, then, thought Frances. She disliked The Times. But there wasn’t the money for a second, less conservative paper. And, in any case, reading the news these days depressed her. In the quaintness of her wartime youth it would have fired her into activity: writing letters, attending meetings. Now the world seemed to her to have become so complex that its problems defied solution. There was only a chaos of conflicts of interest; the whole thing filled her with a sense of futility. She put the paper aside. She would tear it up tomorrow, for scraps and kindling.

At least the house was silent; very nearly its old self. There had been bumps and creaks earlier, as Mrs Barber had shifted more furniture about, but now she must be in her sitting-room—doing what? Was she still in her kimono? Somehow, Frances hoped she was.

Whatever she was doing, her silence lasted right through tea-time. She didn’t come to life again until just before six, when she went charging around as if in a burst of desperate tidying, then began clattering pans and dishes in her little kitchen. Half an hour later, preparing dinner in her own kitchen, Frances was startled to hear the rattle of the front-door latch as someone let themself into the house. It was Mr Barber, of course, coming home from work. This time he sounded like her father, scuffing his feet across the mat.

He went tiredly up the stairs and gave a yodelling yawn at the top, but five minutes later, as she was gathering potato peelings from the counter, she heard him come back down. There was the squeak of his slippers in the passage and then, ‘Knock, knock, Miss Wray!’ His face appeared around the door. ‘Mind if I pass through?’

He looked older than he had the day before, with his hair greased flat for the office. A crimson stripe across his forehead must have been the mark of his bowler hat. Once he had visited the WC he lingered for a moment in the yard: she could see him through the kitchen window, wondering whether or not to go and speak to her mother, who was further down the garden, cutting asparagus. He decided against it and returned to the house, pausing to peer up at the brickwork or the window-frames as he came, and then to examine some crack or chip in the door-step.

‘Well, and how are you, Miss Wray?’ he asked, when he was back in the kitchen. She saw that there was no way out of a chat. But perhaps she ought to get to know him.

‘I’m very well, Mr Barber. And you? How was your day?’

He pulled at his stiff City collar. ‘Oh, the usual fun and games.’

‘Difficult, you mean?’

‘Well, every day’s difficult with a chief like mine. I’m sure you know the type: the sort of fellow who gives you a column of numbers to add and, when they don’t come out the way that suits him, blames you!’ He raised his chin to scratch at his throat, keeping his eyes on hers. ‘A public-school chap he’s meant to be, too. I thought those fellows knew better, didn’t you?’

Now, why would he say that? He might have guessed that her brothers—But, of course, he knew nothing about her brothers, she reminded herself, even though he and his wife were sleeping in their old room. She said, in an attempt to match his tone, ‘Oh, I hear those fellows are over-rated. You work in assurance, I think you told us?’

‘That’s right. For my sins!’

‘What is it you do, exactly?’

‘Me? I’m an assessor of lives. Our agents send in applications for policies. I pass them on to our medical man and, depending on his report, I say whether the life to be assured counts as good, bad or indifferent.’

‘Good, bad or indifferent,’ she repeated, struck by the idea. ‘You sound like St Peter.’

‘St Peter!’ He laughed. ‘I like that! That’s clever, Miss Wray. Yes, I shall try that out on the fellows at the Pearl.’

Once his laughter had faded she assumed that he would move on. But the little exchange had only made him chummier: he sidled into the scullery doorway and settled himself against the post of it. He seemed to enjoy watching her work. His blue gaze travelled over her and she felt him taking her all in: her apron, her steam-frizzed hair, her rolled-up sleeves, her scarlet knuckles.

She began to chop some mint for a sauce. He asked if the mint had come from the garden. Yes, she said, and he jerked his head towards the window. ‘I was just having a look at it out there. Quite a size, isn’t it? You and your mother don’t take care of it all by yourselves, do you?’

‘Oh,’ she said, ‘we call in a man for the heavier jobs when—’ When we can run to it, she thought. ‘When they need doing. The vicar’s son comes and mows the lawn for us. We manage the rest between us all right.’

That wasn’t quite true. Her mother did her genteel best with the weeding and the pruning. As far as Frances was concerned, gardening was simply open-air housework; she had enough of that already. As a consequence, the garden—a fine one, in her father’s day—was growing more shapeless by the season, more depressed and unkempt. Mr Barber said, ‘Well, I’d be glad to give you a hand with it—you just say the word. I generally help with my father’s at home. His isn’t half the size of yours, mind. Not a quarter, even. Still, the guvnor’s made the most of it. He even has cucumbers in a frame. Beauties, they are—this long!’ He held his hands apart, to show her. ‘Ever thought of cucumbers, Miss Wray?’

‘Well—’

‘Growing them, I mean?’

Was there some sort of innuendo there? She could hardly believe that there was. But his gaze was lively, as it had been the night before, and, just as something about his manner then had discomposed her, so, now, she had the feeling that he was poking fun at her, perhaps attempting to make her blush.

Without replying, she turned to fetch vinegar and sugar for the mint, and when the sauce was mixed and in its bowl she removed her hot-pot from the oven, put in a knife to test the meat; she stood so long with her back to him that he took the hint at last and pushed away from the door-post. It seemed to her that, as he left the kitchen, he was smiling. And once he’d started along the passage she heard him begin to whistle, at a rather piercing pitch. The tune was a jaunty, music-hall one—it took her a moment to recognise it—it was ‘Hold Your Hand Out, Naughty Boy’. The whistle faded as he climbed the stairs, but a few minutes later she found that she was whistling the tune herself. She quickly cut the whistle off, but it was as though he’d left a stubborn odour behind him: do what she could, the wretched song kept floating back into her head all evening long.

Taken from The Paying Guests by Sarah Waters

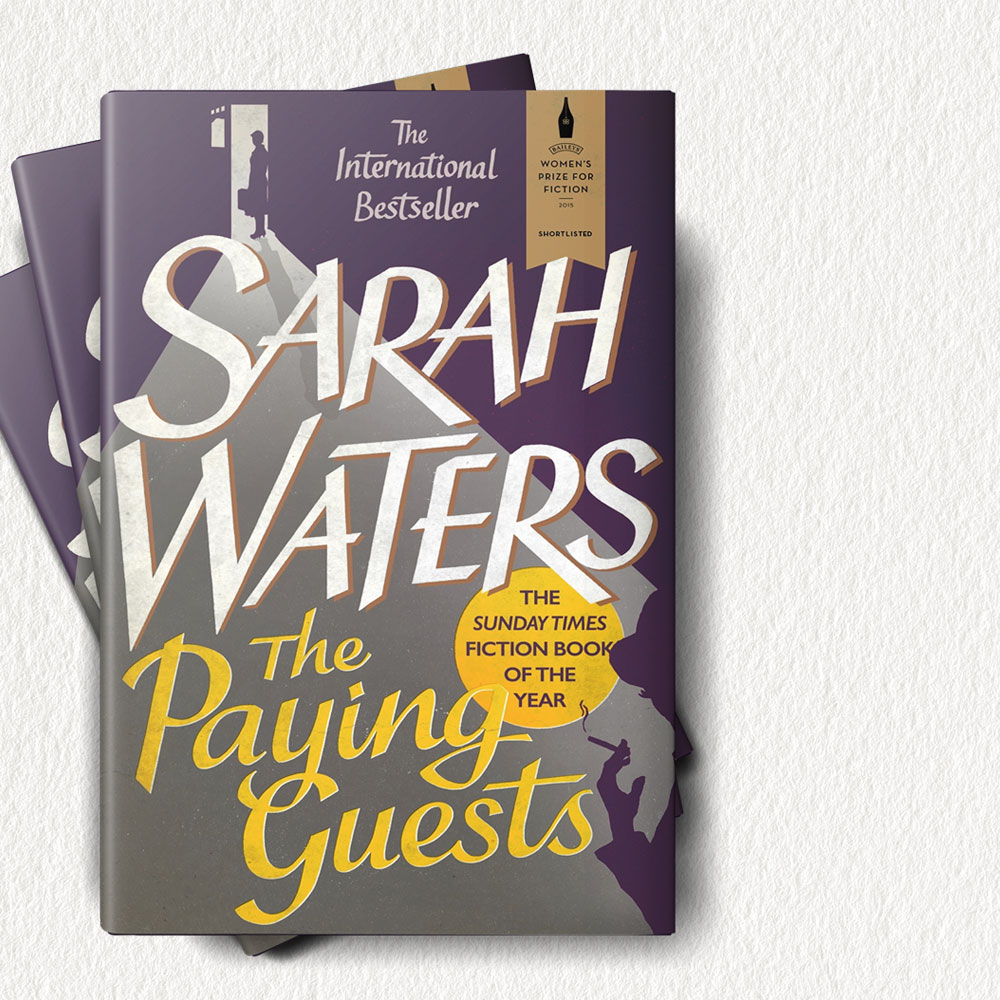

SHORTLISTED FOR THE WOMEN'S PRIZE

This novel from the internationally bestselling author of The Little Stranger, is a brilliant 'page-turning melodrama and a fascinating portrait of London of the verge of great change' (Guardian)

It is 1922, and London is tense. Ex-servicemen are disillusioned, the out-of-work and the hungry are demanding change. And in South London, in a genteel Camberwell villa, a large silent house now bereft of brothers, husband and even servants, life is about to be transformed, as impoverished widow Mrs Wray and her spinster daughter, Frances, are obliged to take in lodgers.

For with the arrival of Lilian and Leonard Barber, a modern young couple of the 'clerk class', the routines of the house will be shaken up in unexpected ways. And as passions mount and frustration gathers, no one can foresee just how far-reaching, and how devastating, the disturbances will be.

This is vintage Sarah Waters: beautifully described with excruciating tension, real tenderness, believable characters, and surprises. It is above all a wonderful, compelling story.

'You will be hooked within a page . . . At her greatest, Waters transcends genre: the delusions in Affinity (1999), the vulnerability in Fingersmith (2002), the undercurrents of social injustice and the unexplained that underlie all her work, take her, in my view, well beyond the capabilities of her more seriously regarded Booker-winning peers. But The Paying Guests is the apotheosis of her talent; at least for now. I have tried and failed to find a single negative thing to say about it. Her next will probably be even better. Until then, read it, Flaubert, Zola, and weep' -Charlotte Mendelson, Financial Times